Angelina Jolie’s decision to have bilateral mastectomies to prevent breast cancer was based on genetic testing. Find out if you should be tested.

I recently interviewed Dr. Noah Kauff, Director of Ovarian Cancer Screening and Prevention, at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, about genetic cancer screening for My Menopause Magazine. I know you will find this information helpful.

Dr. Mache Seibel: Which women should be looking for genetic causes of cancer?

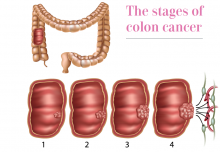

Dr. Noah Kauff: The five most common cancers in women are: breast, colon, ovarian, uterine, and lung cancer and 4 of the 5 are caused by inherited predispositions. Anywhere from five to ten percent of breast, uterine, ovarian, and colon cancer is actually caused by an inherited predisposition that you can get from either your mother or your father.

Dr. Seibel: So, you can grow up with the potential of these diseases and you might not know it. What would be a clue that you actually are a candidate to look for genetic cause of your disease?

4 of the 5 most common cancers in women are caused by inherited predispositions

Dr. Kauff: Things that we’re particularly interested in are: if there’s someone on either side of your family who’s had breast, uterine or colon cancer prior to age 50, or if there’s someone who’s had ovarian cancer at any age. If any of those are in your family history in a close relative – parents, siblings, children, grandparents, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, even first cousins – it may be worth exploring.

Dr. Seibel: So, let me ask you this, what does it mean to get genetic testing for cancer?

Dr. Kauff: Probably, it’s better to think of it as genetic counseling, because genetic testing is a component of counseling. Genetic counseling is a detailed assessment of your personal history and your family history. It can include both whether or not you personally have a diagnosis of cancer, what cancers have occurred in relatives, if there are relatives who didn’t live to be old enough to get cancer, if there are enough relatives in a family to get to show a predisposition.

A genetic counselor, a medical geneticist, or other person trained in cancer genetics will first carefully look at your personal and family history and see whether or not it’s suspicious for the possibility of one of this inherited predispositions. And if it is, there may be genetic testing for cancer. Frequently that is a testing which can be done on a blood sample, although, sometimes, we actually would try and get tumor tissue from someone who has had cancer and we can actually do specific testing on that tissue to help identify if there is in fact an inherited predisposition.

Dr. Seibel: Sometimes a person has no family history but still could have an inherited disease because people could have died too soon. Could you elaborate how the person might know this in their family history?

Dr. Kauff: In that setting, it’s when you personally have a cancer diagnosis but there is no other family history of cancer. For example, a woman with ovarian cancer – and the most common type of ovarian cancer in the United States is something called serous ovarian cancer. It counts about 70% of ovarian cancers but about 90% of ovarian cancer deaths.

Among women who have serous ovarian cancer, approximately 1 in 6 will actually have that cancer as a result of an inherited predisposition, and even individuals who have serous ovarian cancer and have no family history of either early onset breast or ovarian cancer, 1 in 10 will be the result of an inherited predisposition.

Has someone on either side of your family had breast, uterine or colon cancer before age 50?

Such that in 2013, if you yourself have been diagnosed with serous ovarian cancer or a close relative has been diagnosed with serous ovarian cancer even if there’s no other family history of breast or ovarian cancer, it likely makes a great deal of sense to have genetic counseling to see whether or not genetic testing for cancer would be helpful.

Dr. Seibel: So, if you’re a person who thinks you could be at risk for a disease you’ve inherited, how do you go about finding someone to help you?

Dr. Kauff: Start by speaking with your gynecologist. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecology has actually done a large amount of educational outreach towards its membership. There was a Practice Bulletin published in 2009 specifically dealing with the issue of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, and giving specific criteria of individuals who should be considered for genetic risk assessment.

In addition to that, on the National Cancer Institute website, there is a web directory of cancer genetic providers in the United States, and you can put in your state or your zip code and actually identify genetic cancer professionals who are near you and frequently you can contact them directly.

Dr. Seibel: If your doctor is not familiar with genetic risk or not able to help you directly, is there a specific type of person that they should refer you to?

Dr. Kauff: Frequently, it’s going to be a genetic counselor, or it can also be a medical geneticist. A genetic counselor is a master’s trained health professional who have done two years of post-college training specifically in assessing familial risk of a number of different inherited cancer syndromes. They are facile in discussing whether or not there is a potential inherited risk within the family; and if there is, what testing can do to help clarify that risk. And importantly, this is not just to identify risk. If we we’re just identifying risk but we could not do anything about it, this would all actually only be a very academic discussion. But for most of the major inherited cancer syndromes, we now have proven interventions to reduce the risk of cancer in individuals at risk.

Mammography plus MRI improve life expectancy more than mammography alone

Dr. Seibel: What kind of things would you do to intervene, for instance?

Dr. Noah Kauff: Well, for example, women with an inherited predisposition to breast cancer caused by mutation BRCA, the genes, BRCA1 or BRCA2, which are the two most common causes of inherited breast cancer, have a markedly increased risk of breast cancer throughout their life, but also particularly at early ages.

In the general population, about 1 in 50 women would develop breast cancer by the time they are 50.

If you have a mutation of BRCA1 like Angelina Jolie or BRCA2, as many as 1 in 4, to 1 in 3 women will develop breast cancer by the time they are in their 50s. The breast cancer can start as early as the mid 20s, and for these groups of women, rather than just starting mammography at age 40 which is what is recommended for the general population, we actually start with the combination of both annual mammogram and annual breast MRI starting no later than at age 30.

There are also medications to reduce the risk of cancer and we can also talk about surgical risk reduction strategies. It turns out prophylactic mastectomy is an option for BRCA patients, and although that may seem like a drastic option, for someone who has lost three, four or five individuals in her family to breast cancer, it is something which is an option that’s actually taken by about 1 in 3 women with these inherited predispositions.

Dr. Seibel: So, if you have a gene for instance, for breast cancer, it’s not something that you have to do? It’s something that you may be offered and you can choose to do it, or not do it?

Dr. Kauff: Absolutely. Because we have two very good approaches for reducing breast cancer risk in the setting of inherited predisposition. The combination of intensive screening with mammography and breast MRI has been shown to be better at detecting inherited breast cancer than mammography alone, and improve life expectancy more than would be the case with mammography alone.

Dr. Seibel: So, the bottom line is, if you have a family history of people in your family dying of cancer before age 50, that’s a very important clue, and you should see a genetic counselor.

Dr. Noah Kauff: And the one thing is, it’s not even dying before age 50, it’s being diagnosed before age 50 and that would be for breast cancer, colon cancer, or uterine cancer. Importantly, ovarian cancer does not have to be early onset. For anyone who has a family member who’s either been diagnosed with or died of ovarian cancer at any age, it is worthwhile to speak to your doctor about the possibility of genetic risk assessment.